Decoding biology with functional genomics

🧬 🔢 Gathering quantitative genotype → fitness data at scale: Part 2

Introduction

Biology is famously complex, but we’re seeing that data at scale can give us a bird’s eye view of everything from the function of specific genes to the deep biological complexity of how those genes interact. In our previous post, we laid out the basic machinery of our functional genomics platform: fragment genomes, insert into a host strain to simulate horizontal gene transfer (HGT), measure fitness under selection, and use sequencing to build a genome-wide fitness map. As we continue these experiments, we’re beginning to see that the data reveals deep complexity in the underlying biology. We’ve come up with three vignettes about how genetic context, evolutionary distance, and library design shape the outcomes of functional genomics.

In this post, we’re sharing three lessons we’ve learned recently about functional genomics:

Neighbors matter! Sometimes beneficial genes can be tricky to spot when they are adjacent to detrimental genes.

Data acquisition at scale is possible. A single library can cover tens or hundreds of donor genomes, dramatically increasing throughput.

AI may help. Protein similarity is a good predictor of HGT success, and utilizing DNA language model embeddings may even improve prediction success.

By understanding the underlying capabilities and requirements of HGT, we are starting to understand the explanatory power of this kind of functional genomics for decoding biology. Future datasets may cover hundreds of organisms in tens of contexts, and by understanding what kind of data is useful we’ll be better able to ensure that those datasets are as rich as possible.

🔪 Dissecting the Effect of Genomic Context on Gene Fitness

We previously demonstrated that with a high-coverage genomic fragment library we can map fragments to genomic position and get a high resolution fitness readout of individual genes in a donor genome. With this sort of visualization, we found that the top hit in our H. elongata library was the gene galE, when inserted into E. coli and selected in a high-salt environment.

As a next step, we wondered if our libraries had high enough coverage to examine epistatic dependencies. With a library size of almost a million fragments, most genes will be covered by at least several fragments. Thus, could we detect fragments whose fitness strongly depends on the precise composition of present genes?

More precisely, we asked the following question: “Does our assay yield any fragments who register as fitness hits only if they cover a single gene, and not neighboring genes?” To calculate this, we recomputed our genomic fitness map where we defined the fitness of a gene as the mean fitness of all inserts covering that gene. However, this time we only used inserts that fully covered a single gene. So, now the fitness of each gene is defined purely by inserts that only cover that gene and not its neighbors.

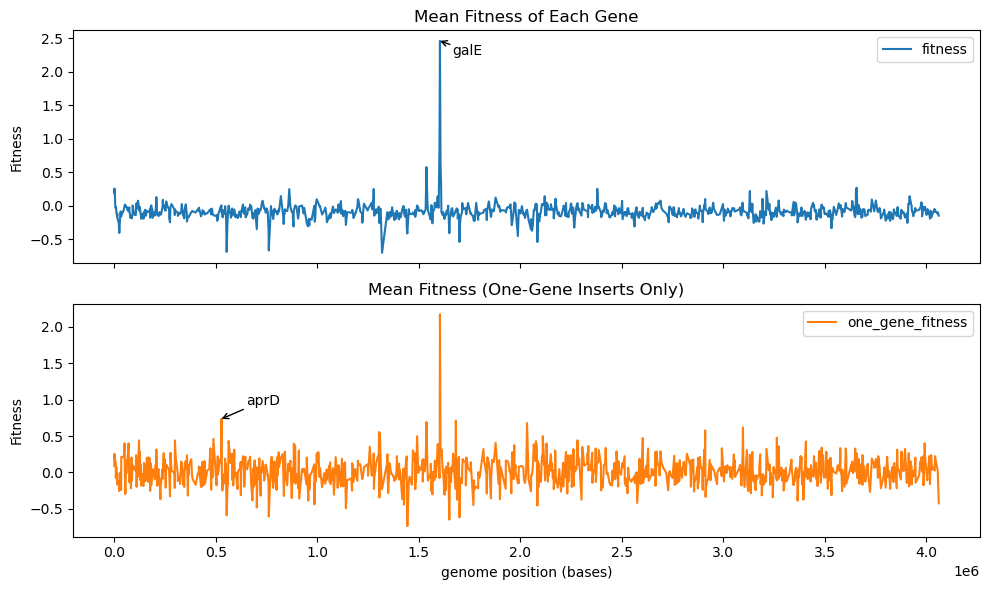

In the plot below, we compare the previous genomic fitness map (top) with this single-gene-insert map (bottom). galE shows up as the top hit in both cases. Interestingly, the bottom plot shows a few medium peaks that do not appear in the top plot. This indicates the presence of genes that only contribute to fitness when their neighbors are not present! As an example, we annotate the gene aprD, which has a computed fitness of near zero when considering all inserts but has a mild fitness gain of near 1 when only considering inserts that only cover aprD itself. aprD is an alkaline protease secretion ATP-binding protein1.

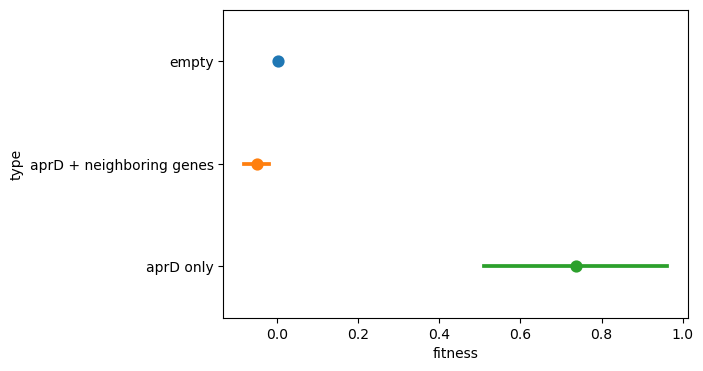

To verify this finding, we directly plotted the fitness distribution of all inserts covering aprD (including neighboring genes) and compared this with the distribution of inserts that only cover aprD itself. We see that in the former case, the fitness is very similar to the null fitness of the empty inserts, whereas in the latter case, the fitness is relatively high around 0.8 (corresponding to a fold-change of nearly 2).

Thus, our libraries have enough coverage that for a single donor genome, we can actually dissect position-dependent effects! In this case, we found an example of a gene that contributes to fitness only when found in isolation. If neighboring genes are included, the fitness gain actually drops out. Moving forwards, this indicates the importance of being sensitive to epistatic dependencies in our fitness hits.

🍲 Generating Pooled Libraries to Better Screen the Microbial World

One of our scientific goals is to leverage the genetic diversity of the microbial tree of life to source uncommon DNA for engineering polyextremophiles suitable for Mars. Traditionally, we built large, high-coverage libraries from single donor genomes. However, we came to realize that with average insert sizes of ~5 kb and bacterial genomes of ~5 Mb, our 106 libraries are large enough to achieve sufficient coverage from multiple genomes within a single library. Our pooled library strategy enables higher-throughput construction, faster screening, and broader sampling of the microbial tree of life, particularly from unculturable microbes from e.g. metagenomic samples.

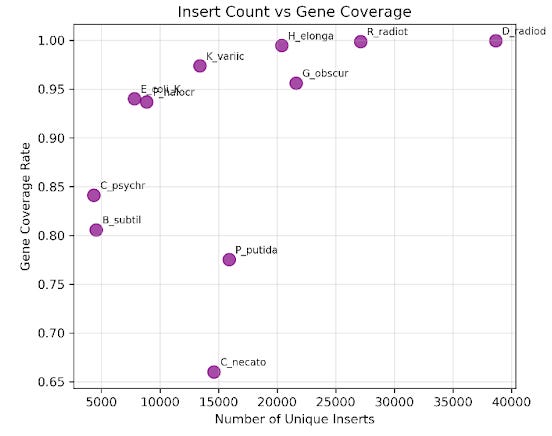

For an overview of how we originally built our libraries, see our previous Substack, The First Turn of Our Engineering Crank. To test whether pooled libraries could provide good coverage across multiple genomes, we began with eleven donor species representing both gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria. We developed a barcoding system to computationally track the various donor genomes in our pooled library2. After normalization and pooling together in equimolar ratios to create a single and complex pooled library representing all donor genomes, we electroporate into a cloning strain, allowing us to capture a diverse array of genomic fragments in a single, multiplexed transformation. Our first pooled library had relatively even and comprehensive coverage of each donor genome – on average, each genome had more than 80% coverage and over 15,000 unique inserts associated with it.

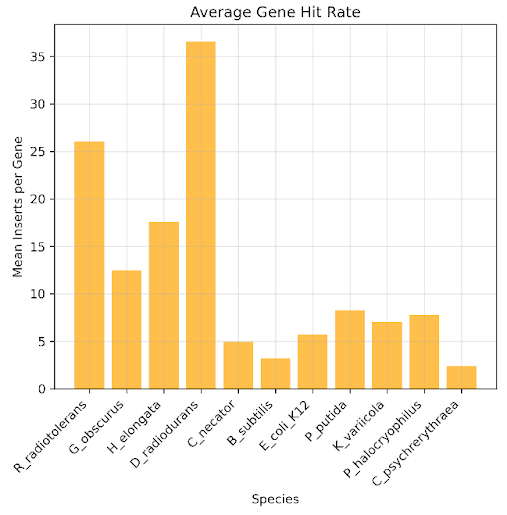

In downstream analysis, we want to characterize each gene with a fitness score from a selection experiment. Crucial to that computation is statistical sufficiency, i.e. does each gene contain enough inserts to calculate a fitness score? Below we plot the average number of inserts that fully contain each gene for each donor genome. We see that while there is variability, most genomes have close to 10 inserts covering each gene on average.

In the future, we plan to scale up to pooling up to 100 genomes in a single library. To get there, we’ll want to improve the evenness and coverage of our pooled libraries to get better representation of each donor genome, for example through normalizing by genome size.

🔍 Identifying Determinants of Gene Transfer with a Complementation Assay

While the primary use of our platform is to identify extremophilic DNA fragments that confer a fitness benefit in harsh selection conditions, we can also repurpose the platform to study aspects of basic biology. Inspired by previous auxotrophy complementation analyses, we leveraged our crank to study aspects of horizontal gene transfer. Specifically, we used a complementation assay where we conjugated our 11-genome pooled library described above into an E. coli auxotroph with the core gene dapA knocked out3. We wanted to know if dapA homologs rescue endogenous dapA function in a way that is correlated with homology.

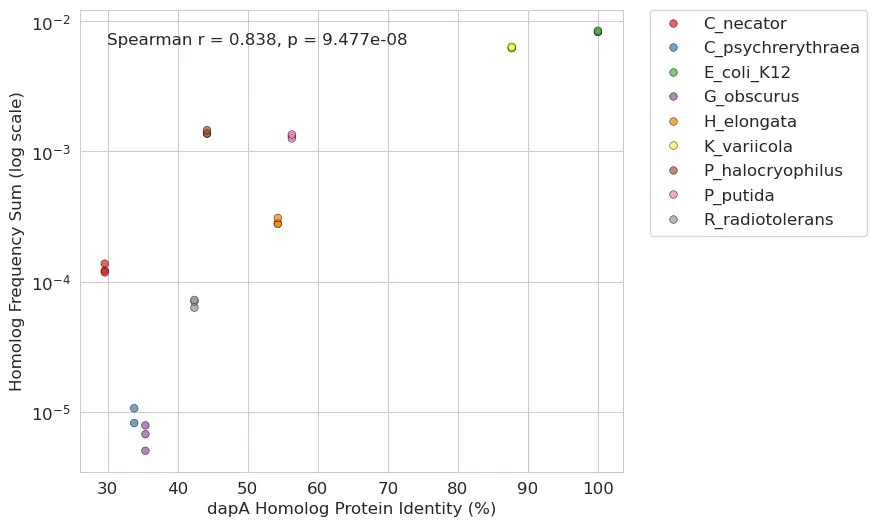

To tackle this, we first annotated all dapA homologs across the species in our pooled library as well as the inserts that contained them. For each homolog, we calculated its protein identity similarity to the endogenous E. coli gene as well as the average insert frequency at day 0 of our experiment (a proxy for gene transfer success). dapA homologs with high similarity to the E. coli dapA were very fit. For example, K. variicola’s dapA possesses about 90% protein similarity with E. coli and got the second-highest overall frequency. However, we also saw that the dapA homolog from C. necator, a phylogenetically distant relative of E. coli with less than 30% protein identity, still rescued the auxotrophy.

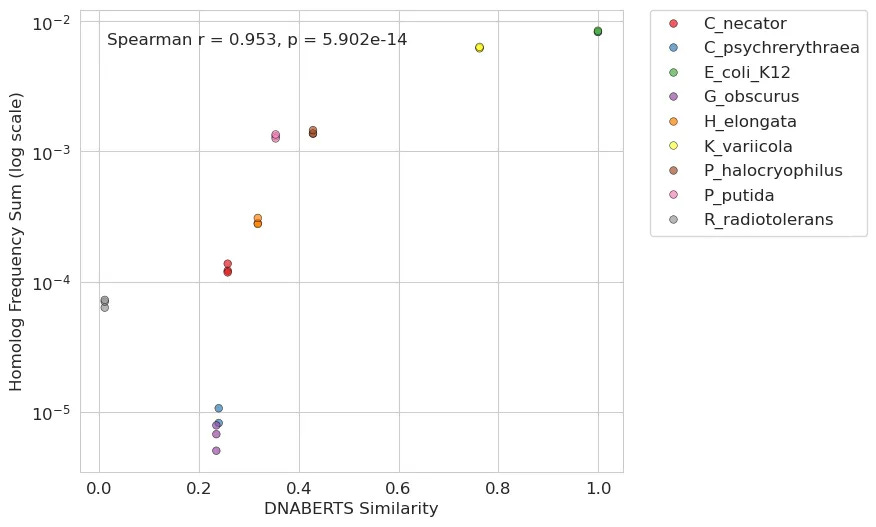

Building on these initial findings, we were curious if we could utilize more contemporary DNA language models to extend the analysis beyond simple protein similarity. Specifically, we used DNABERT-S, a model trained on extensive genomic data, to create high-dimensional embeddings for each homolog gene sequence. These embeddings can capture intricate patterns and relationships within stretches of DNA and may offer a more detailed (yet abstract) comparison than conventional sequence alignment. Our approach compared the sequence embedding of each homolog to the E. coli gene using cosine similarity where higher scores indicate a greater degree of similarity. This led to an even stronger positive correlation: the closer a homolog’s sequence embedding was to that of the E. coli gene, the more effectively it was able to rescue the auxotrophy.

Our dapA complementation experiment proved to be a valuable experiment for studying the factors influencing HGT success and functional rescue. This data allowed us to show a clear relationship between the similarity of a dapA homolog to the endogenous E. coli gene and its ability to rescue auxotrophy. At the same time, we did not have enough data points to try to model HGT quantitatively and there were some outliers (e.g. C. necator). In the future we would like to design larger experiments with 100+ homologs present to start building more sophisticated models of HGT. This provides a powerful opportunity for predicting gene transfer and functionality, even from phylogenetically distant organisms, as well as for applying modern DNA or protein language models.

Conclusion

These three results sharpen how we use HGT as a tool. Epistasis between adjacent genes can show up in our large-fragment libraries, pooled libraries let us multiplex many genomes in one experiment, and ML-derived sequence embeddings give us a better handle on which genes will work in new hosts. Those are exactly the ingredients we need as we push to much larger datasets—turning HGT-based functional genomics into a practical way to mine the microbial world for parts and assemble microbes suited for Mars.

1 The actual gene in H. elongata is unannotated, and the aprD annotation comes from a BLAST protein search.

2 During cloning, we add organism-specific 8 bp barcodes when amplifying the barcoded backbone, creating uniquely indexed vectors that preserve the genomic DNA (gDNA) source. After characterizing our libraries with long-read PacBio sequencing, instead of aligning millions of inserts against all reference donor genomes at once (a very computationally demanding task) we first use the 8 bp barcode to identify the source organism, then align only to that genome. This sharply reduces the search space, improving speed, accuracy, and computational efficiency. While the benefit is modest with eleven genomes and requires additional front end work, this strategy will be essential as we scale to future massive data collection experiments consisting of pooled libraries containing up to 100 donor genomes.

To maintain clear separation between genomic sources during library construction, we work with uniquely 8 bp barcoded vectors and gDNA independently. Each organism’s gDNA is fragmented and cloned into its corresponding vector containing the matching barcode. Only after ligation are the barcoded libraries pooled, ensuring that all inserts are correctly linked to their source organism. Before electroporation into our cloning strain, we normalize each barcoded library by concentration to achieve balanced representation and prevent any single donor from dominating downstream cloning or sequencing.

3 This complementation assay was actually an unintended experiment! In our crank, we conjugate our libraries into recipient strains to genomically integrate library fragments. Our conjugation host, E. coli MFDpir, is an engineered diaminopimelic acid (DAP) auxotroph, meaning it is genetically dependent on an external supply of DAP for survival. We intended to use DAP withdrawal to impose a strong negative selection to eliminate the host cells following conjugation. However, our multi-species genomic library contained genes like native dapA or functional homologs that were capable of DAP biosynthesis. When these fragments were horizontally transferred into MFDpir, they successfully rescued the auxotrophy by restoring the missing pathway and allowed these host cells to survive and grow even in the absence of DAP supplementation. This unintended functional complementation event, while contaminating our primary screen, provided a unique opportunity to study complementation. It created a pseudo-auxotrophy experiment that allowed us to study the genomic factors that underlie HGT success.

This is really neat! Are you looking at deleterious genes as well, i.e those which provide fitness defects? Seems useful to see if most genes are "background" or if some are genuinely negative.

Also - for your 11 different microbes- are those all for salt tolerance? Or are those a range of cultured bugs you expect to have at least one of the five conditions for Mars tolerance? I see radiodurans in there so I assume it's all conditions. I wonder what the expected % of E coli transformants you expect to see for any combination of conditions... I bet astronomically low. Super cool work. Excited to see what you guys do next!